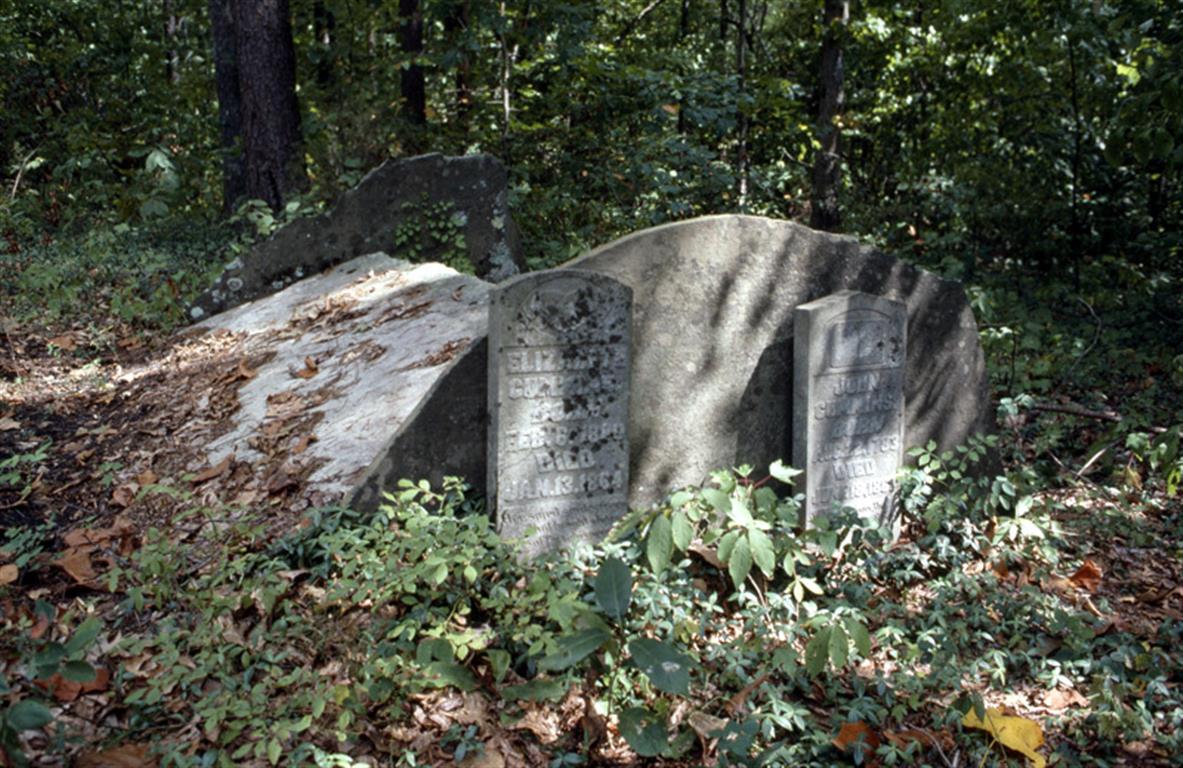

Most comb graves feature a headstone that is separate from the comb structure, and some feature both head- and footstones. These head- and footstones typically are of the same local stone as the comb; this is especially true of the older comb graves. However, it is not rare for the headstone to be of marble or other non-local “store-bought” stone. Some combs, especially in the older comb cemeteries, are “headless” (Plate 2). Many of these headless combs have no inscriptions, making it difficult to know who is covered by the comb or when the burial occurred. However, some headless combs have inscriptions on one side slab (Plate 3a) and a few have inscriptions on one of the gable-end stones (Plate 3b).

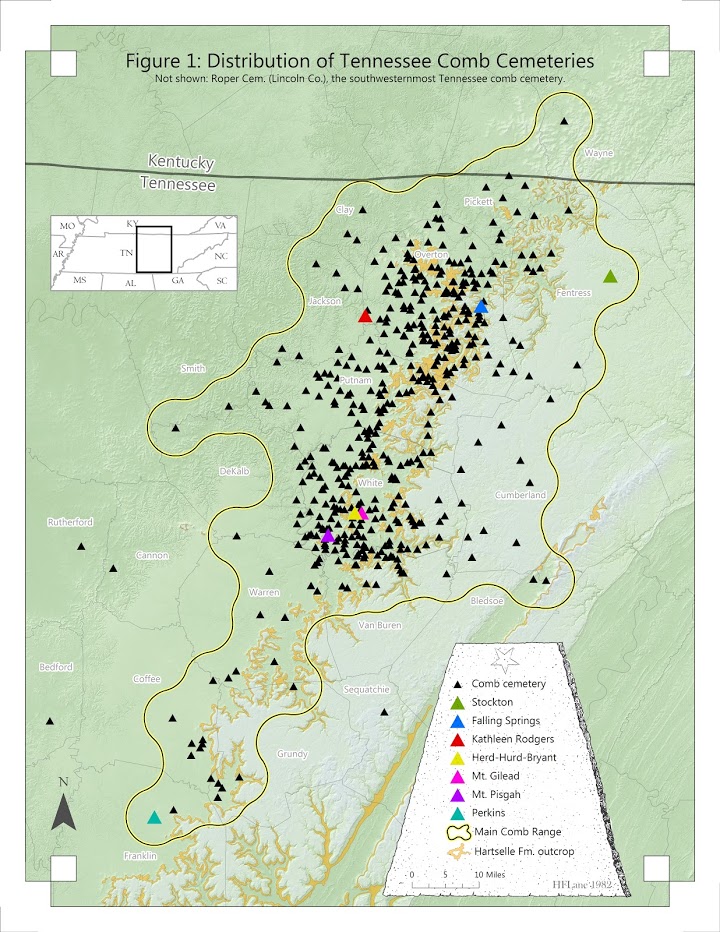

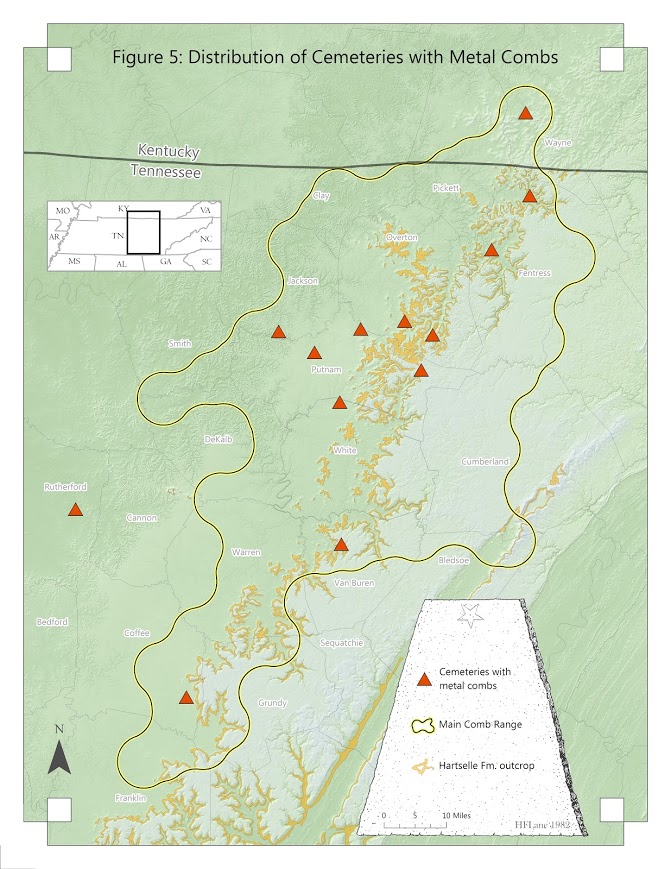

In Tennessee, over 3600 extant combs are found in over 500 cemeteries scattered along a NNE-SSW-trending band paralleling the western front of the Cumberland Plateau (Figure 1 shows the distribution. N.B.: Since this figure was prepared for publication, a number of additional comb cemeteries have been located; for a continuously updated map showing all the known comb cemeteries, see Chuck Sutherland's interactive comb cemetery map found on www.graterutabaga.com). Comb graves are most common in older graveyards lying on the Eastern Highland Rim, below the Plateau. However, many are also found on the Hartselle Bench halfway up the Plateau escarpment, and a lesser number on top of the Plateau along its western side. The southernmost examples in the main Tennessee comb range are 13 combs in Perkins Cemetery just northeast of Winchester, in Franklin Co. Roper Cem., in Lincoln Co., well to the west of the contiguous Tennessee comb range, boasts the south-westernmost combs known in the state (not shown in Figure 1). The northernmost extant example is a single comb in Rector Cem. in Pickett Co.2 However, one additional comb grave formerly existed in Taylor's Grove Cem. 8.6 miles north of the Tennessee-Kentucky state line, and this cemetery should still be considered part of the geographic range of the Tennessee comb graves.

The tradition of erecting combs over graves appears to have commenced around 1815 -1820. The custom was strong throughout the remainder of 19th century and during the first half of the 20th century, but by the 1950s-60s erection of combs was uncommon. Even so, a comb was erected in 2012 (Finch, 2013).

Comb graves are known to be present in nine other Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, West Virginia, Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, North Carolina and Georgia). A few comb graves have also been found in eastern Oklahoma and southernmost Missouri, areas that are culturally part of the Upland South (Jordan-Bychkov, 2003). However, Tennessee has more known comb cemeteries and comb graves than all the other states combined. Additionally, the oldest known combs are found in Tennessee graveyards. Probably, the comb grave custom is indigenous to Tennessee.

A variety of ideas have been suggested to account for the “why” of combs, i.e., the purpose served by placing a comb over a grave. Protecting the grave seems to have been a motive, but there is no definitive single reason for combs. It is likely that different reasons motivated different people to erect combs, but that ultimately the comb became a highly popular style, indeed the dominant grave style in numerous small graveyards within the comb range. And style alone was probably sufficient reason for many. Of the other various well-known types of grave covers (ledger stones, box graves, stone table markers, gravehouses, coffin graves, and cairn graves) within the main comb range, none were used in numbers comparable to the comb graves.

Many county road maps contain cemetery location information. For some Tennessee counties, maps have been published for the exclusive purpose of showing cemetery locations. Comprehensive cemetery books have been written for a number of counties, e.g., Overton, White and Van Buren counties. The “Fred Clark Book of Cemeteries of White County” proved exceptionally useful inasmuch as it denotes which cemeteries contain comb graves. Online cemetery maps are available for some counties, but the locations given are not always correct. Two online sources that have proved especially useful are Find-A-Grave ( www.findagrave.com ) and the Tennessee Property Viewer ( https://tnmap.tn.gov/assessment/ ). Find-A-Grave can be mined for leads to cemeteries, but must be used with caution as much information on this website is incorrect, especially cemetery location descriptions. The Property Viewer can be used to search for additional cemeteries because many graveyards are deeded apart from the adjacent or surrounding parcels. Such cemeteries show up as unusually small parcels, often completely surrounded by a larger tract; when a “postage stamp” parcel is spotted on the property viewer map, the “identify” function can be used to determine whether or not it is a cemetery. Somewhat surprisingly (or perhaps not?) this state government website also is troubled with some incorrect property lines and even completely mis-located parcels.

With the numerous and varied sources available, it is clear that the quest --already over four decades old-- to locate all Tennessee comb cemeteries is a task that can never be truly completed before the writer himself is in need of a comb. But the search goes on!

In sum, for this survey, all cemeteries --excepting those that have disappeared3-- on 129 quads have been visited and any combs noted. Out of a total of over 3100 cemeteries, exactly 517 comb graveyards have been identified in the main comb range, and 3663 extant combs counted and photodocumented. The 517 comb cemeteries include 471 graveyards that currently contain combs and 46 ex-comb graveyards known to have formerly had combs. Ex-comb cemeteries were mostly identified in two ways: 1) they had combs when first visited, but the combs were gone on a subsequent visit; 2) they contained clear-cut remnants of comb graves, e.g., a matched pair of triangular gable stones indicating the former presence of a comb. Historic photographs showing combs in graveyards that no longer feature comb graves facilitated the identification of three former comb cemeteries. Graves with only a single triangular stone, or a single rectangular slab laid flat, or sets of head- and footstones of a style commonly associated with comb graves were noted as “probable” or “possible” ex-combs, depending on the evidence, but were not counted as definite ex-combs. Cemeteries with only possible or probable ex-combs were not included in the total number of comb cemeteries, even though at least some of them surely once were comb cemeteries. Appendices A-1 and A-2 are inventories of all the comb cemeteries, ex-comb cemeteries, and combs surveyed.

The locations of the comb cemeteries listed in Appendices A-1 and A-2 are given in latitude and longitude, recorded in the field with a GPS unit (set to the NAD-27 datum, the datum of the published maps) or measured from the published quads (using a TopoTool Coordinate Ruler by Neff Scientific). Where the local name for a cemetery was not known, a name was given for the purposes of this survey based on the most prominent surname or surnames in the cemetery.

To ensure that the full contiguous range of comb graveyards was defined, the survey was extended into quads beyond the core geographic area of the combs until a border of “comb-free” quads was established around the entire contiguous comb range.

Having commenced as a purely geographic endeavor, this study eventually morphed to incorporate more aspects of the comb grave tradition: its temporal range, physical materials used, church associations, origin and reasons for the custom. If a number of comb cemeteries have been missed by this survey, as they most certainly have been, some of the statistics presented in this paper will be changed when these overlooked cemeteries are ultimately discovered and reported. Nonetheless, for the present, we can be relatively confident that the geographic range has been defined and documented, and insights gained regarding other aspects of the comb tradition.

A very few instances are known where sandstone side slabs have been beveled to meet neatly at the crest of the comb (Plate 7). This nice bit of stone dressing probably is practical mainly where thicker than normal sandstone slabs are employed4.

While gable stones are the most common form of support for the comb side slabs, a noteworthy alternative support system involved the use of a thick iron rod running the full length of the grave. The rod, actually a long bolt, has a head at one end and is threaded at the other end. A hole was bored through the headstone and another carefully positioned hole through the smaller, but stylistically matching, footstone (Plate 8). Typically, the bolt was run through the headstone first and then through the footstone. The heavy nut was then turned onto the threads behind the footstone. Probably, the sideslabs were laid before the nut was fully tightened, allowing the head- and footstone positions to be adjusted slightly if needed to mate with the side slabs. In any case, one side slab (typically the right) was laid on the bolt rod itself, and the second side slab (typically the left) was laid against the upper end of the first laid slab (again resulting in lapped comb slabs). When all four stones were in place, the nut could be tightened to draw the head- and footstones tight against the ends of the side slabs. In this system, no supporting gable stones are necessary under the side slabs, but the system requires both head- and footstones, and the holes for the rod had to be accurately placed.

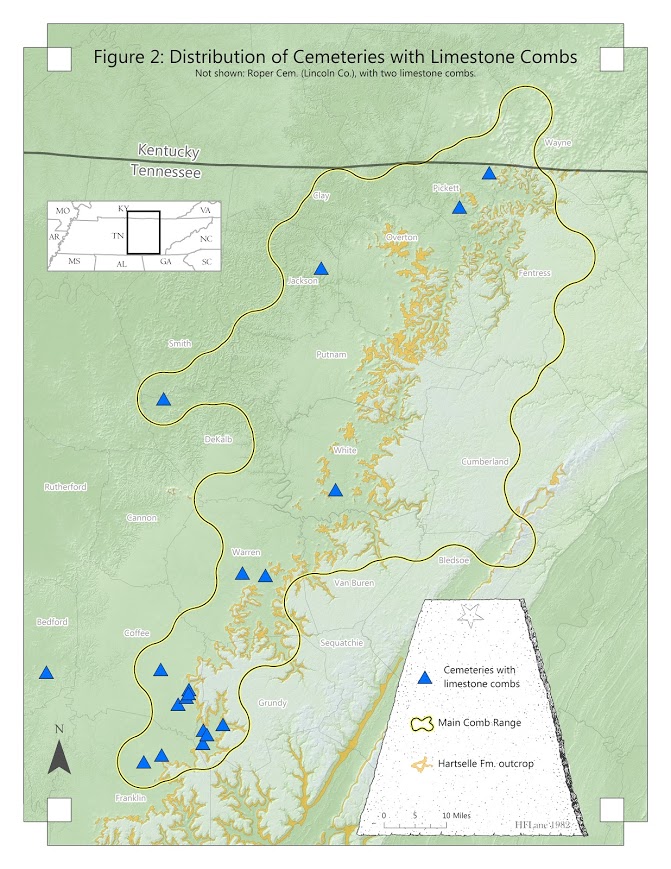

However, where appropriate sandstone was unavailable, other materials came into play, notably limestone. Limestone is not commonly planar-bedded, and, for that matter, is more often thicker bedded than thin. Nonetheless, limestone (or, in one instance, dolostone, a magnesium-rich variant of limestone) was used for at least 63 combs in 24 cemeteries, primarily where sandstone evidently was not locally available. Some of the limestone combs are made of very finely dressed stone (Plate 10). The thicker limestone slabs sometimes feature beveled edges (Plate 11) or other innovative shapes (Plate 12) In other cases the limestone combs are relatively crude (Plate 13). Phillips Cem. (Hillsboro quad, Coffee Co.) features three limestone combs along with ten combs made of rather rough, thick-bedded sandstone slabs.

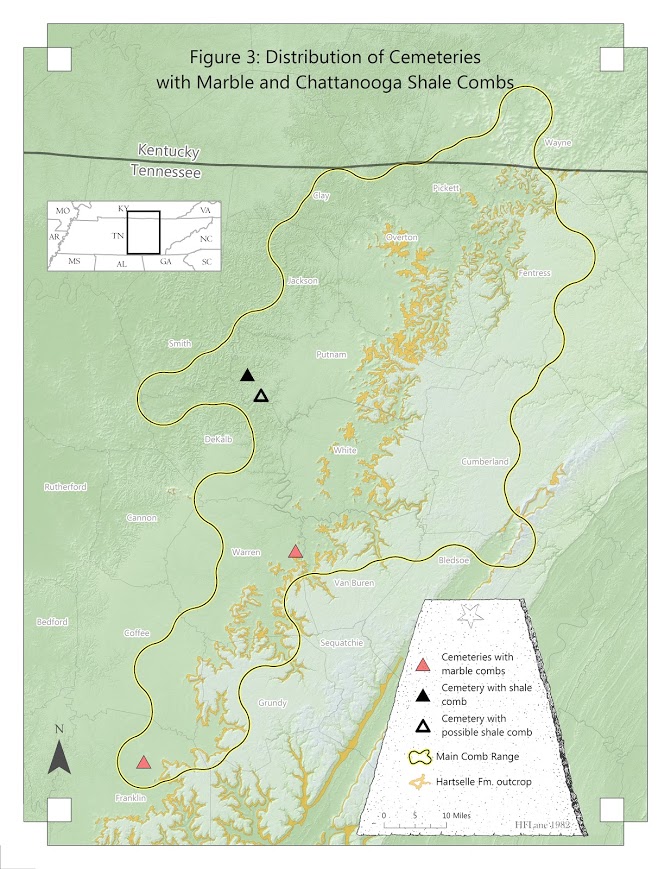

The Chattanooga Shale is a very distinctive rock unit, easily split into thin, planar, black slabs that are attractive when fresh. This feature, plus the fact that it was locally available, probably free for the taking, may explain its use on this grave. Unfortunately, the Chattanooga is so friable that extracting a slab big enough to run even the length of an infant’s grave would have been difficult and this crude comb appears to have been constructed of several relatively small pieces. Additionally, the black shale contains fine grains of pyrite (iron sulfide) which weather easily and promote the relatively rapid disintegration of the shale. Therefore the Chattanooga Shale is not a good choice for grave markers, in spite of its fissility.

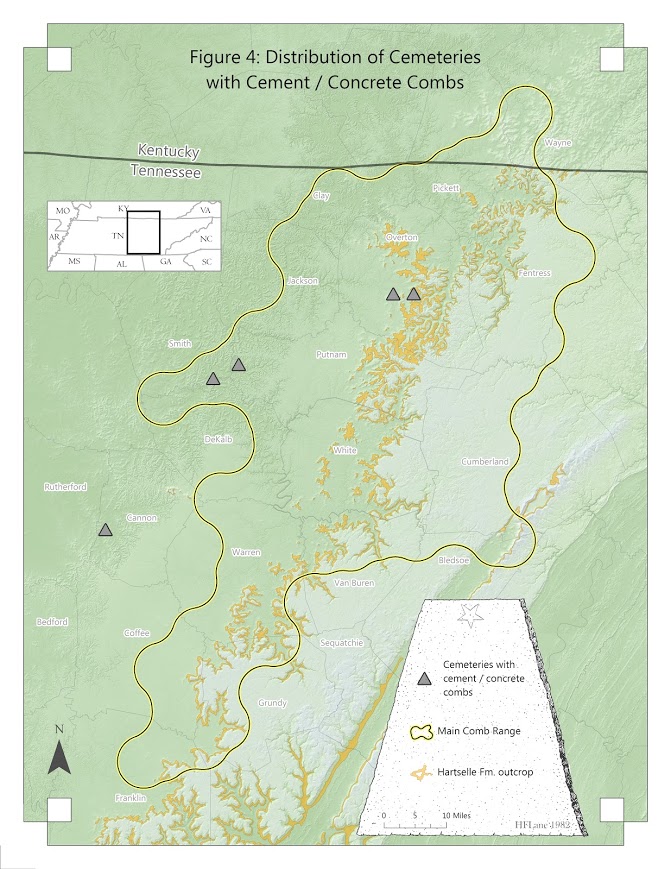

One of the striking characteristics of all these cement/concrete combs is that they are molded to mimic the basic form of two slabs resting on triangular gable supports, just like ordinary sandstone combs.

Being supported by wooden frameworks, metal combs are obviously not as durable as stone combs. Of the 26 metal combs known, around a half dozen seen during the early stages of this survey have since collapsed or otherwise been destroyed.

The Hartselle Formation is a stratigraphic unit deposited during the Mississippian Period (350-299 million years before present). Its type section is near Hartselle, Alabama. In Tennessee the Hartselle crops out along the eroded western slopes of the Cumberland Plateau, where it forms a continuous north-south outcrop band across the state, typically at elevations around 1100 –1400 ft. (The Hartselle outcrop trace is shown in the figures.) It is also found in many erosional outliers of the formerly more extensive Plateau, such as Gum Spring Mountain, just west of Sparta.

The Hartselle Formation consists mainly of sandstone and shale, with the relative proportions of the two rock types varying significantly over the length of its outcrop belt. Where well-indurated, quartz-cemented sandstone is prominent, the Hartselle forms a resistant unit which erodes more slowly than the overlying Bangor Limestone. As the Bangor is eroded back, a nearly flat topographic surface, known as the Hartselle Bench, is formed on top of the Hartselle. Where well developed, the Hartselle Bench forms a distinct stair-step in the western escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau. The Hartselle Bench also forms the flat upper surface of various of the erosional outliers lying to the west of the main Plateau. It is in these areas, where the Hartselle Formation contains significant amounts of sandstone, that the comb graves are found in abundance.

South of Warren county, the Hartselle Formation becomes more shaly, with a lower sandstone content8. It is in this region that most limestone combs are found. Not much further to the south, the Tennessee combs die out.

The Hartselle Formation is not found on the east side of the Cumberland Plateau; nor are any combs found here.

The range of the Tennessee combs also dies out a little north of the Tennessee-Kentucky line, for reasons that are at present obscure. Nonetheless, it is fair to say that in Tennessee, the comb grave tradition was strongly influenced by the presence or absence of appropriate sandstone in the Hartselle Formation, and that the primary control on the geographic range of the combs was the lithology of the Hartselle.

In sum, combs are found in graveyards on the Hartselle Bench, in cemeteries along the western portion of the Plateau relatively close to the Hartselle outcrop band, and on the Eastern Highland Rim below the Plateau. Combs become rarer (or made of substitute materials such as limestone, concrete and sheet metal) in areas distant east or west of the Hartselle outcrop band, the distance likely related to the difficulty of moving the heavy stones via 19th- and early 20th-century transportation facilities.

Doyle quad (White and Van Buren counties) contains 38 comb cemeteries (the 2nd greatest number of comb cemeteries in a single quad), with a total of 546 extant combs, by far the highest comb count for a single quad. The adjacent Cassville (34 comb cemeteries) and Bald Knob (29 comb cemeteries) quads have comb counts of 422 and 350 respectively. Thus, these three quads alone account for 36% of the 3663 extant combs in the main Tennessee comb range. Not surprisingly, these three quads also contain the individual cemeteries with the highest comb counts: Mt. Gilead Cem. (Cassville quad), 138 combs; Mt. Pisgah Cem. (Doyle quad), 126 combs; Old Union Cem. (Bald Knob quad), 102 combs.

Combs are numerous in Overton Co., with Crawford quad presenting the highest comb cemetery density of any quad: 23 out of 24 cemeteries, i.e., 96%, have combs, for a total extant comb count of 435, the second highest count of any quad. The Falling Springs Cem., with a comb count of 102, is located in the community of Allred, as is the old Vaughn stone quarry, source of so many comb rocks. Okalona quad contains 45 comb cemeteries, the highest number of any quad, and has an extant comb count of 387. Thus the Crawford and Okalona quads alone account for 22% of all extant combs in the main Tennessee comb range.

Including these outliers, the total number of Tennessee comb graveyards rises to 521 and the total number of extant combs to 3669. A statewide search would undoubtedly reveal more comb graves, but these scattered instances of combs--likely the result of the practice being introduced by families migrating westward from the main comb region—do not represent a widespread coherent local tradition in these areas.

Several sheet metal combs in Pierce Cem. (Obey City quad, Overton Co.) are likely younger than the graves they cover, as suggested by the apparent newness of the wooden frames supporting the combs. Four cement combs in Lancaster Cem. (Buffalo Valley quad, Smith Co.) are all structurally connected and appear to have been constructed concurrently, some time after the most recent date of death, 1921, which is some three years after the earliest date of death, 1918. In Stockton Cem. (Stockton quad, Fentress Co.) there are five headstones with dates ranging from 1847 to 1862, that all appear to be the work of a prolific stonecutter who operated in the White Co. area. A Stockton family tradition holds that these stones were brought on an oxen-pulled sled from White Co., an exceptionally long and tedious trip for hauling gravestones. It is thought by a Stockton family member9 that all five stones were probably commissioned and brought to the family burying ground at the same time. This assumption is far more reasonable than assuming that five separate trips were made over such a distance (66 miles by today’s highway system). If true, then at least one of the Stockton combs was erected 15 or more years after the date of death.

In spite of the foregoing examples, unless there is evidence to the contrary, the year of death inscribed on a comb grave is considered to be the date of the comb itself.

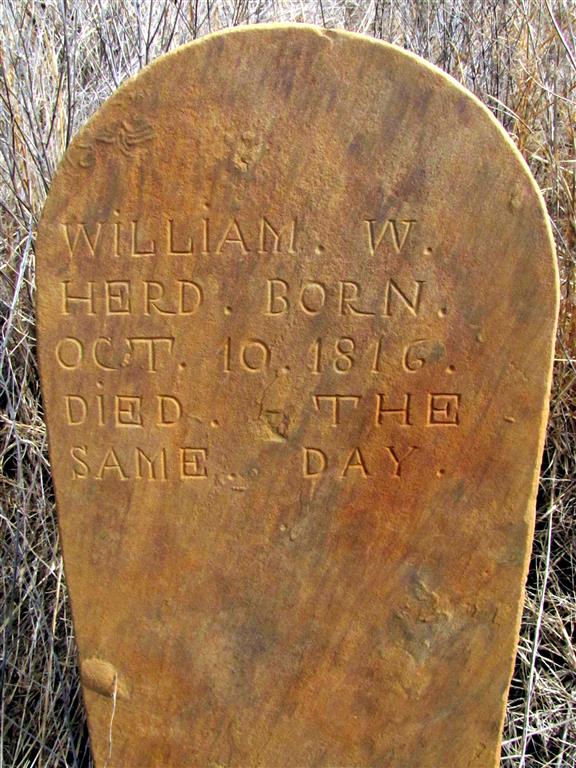

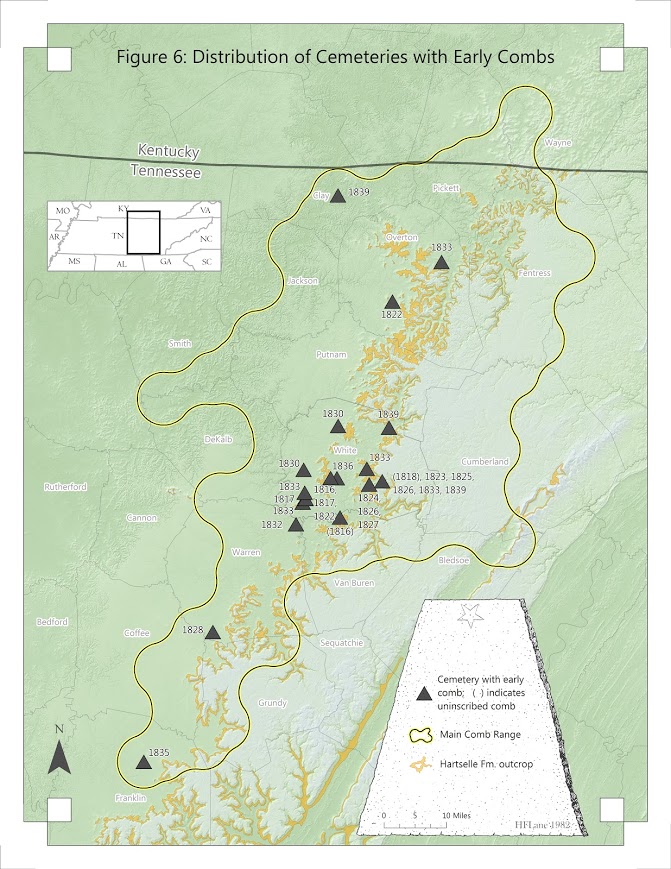

The earliest dated comb grave thus far found is in the Herd-Hurd-Bryant Cem. (Cassville quad) in White Co., the comb of William W. Herd, who was “Born Oct. 10, 1816, Died the Same Day” (Plate 21). Remarkably, this same small cemetery also contains combs dated 1817 and 1822 --the 2nd and 3rd oldest comb dates—in the same row of graves with the 1816 comb. The 1816 and 1822 combs have simple round-topped headstones, whereas the 1817 comb (Plate 22) features a necked discoid headstone (McNerney, 2017).

In an earlier version of this paper, it was stated that the comb grave of Rosey Hutson, found in Mt. Pisgah Cem. (Doyle quad, White Co.) bore the oldest known date on a comb, 1817, inscribed on a headstone of the necked discoid type. However, based on stylistic considerations, it was thought that this particular comb was likely erected some years after the death date10. The discovery of the Herd-Hurd-Bryant Cem. with a second necked discoid dated 1817 (Plate 22) renders it more likely that the 1817 date in the Mt. Pisgah Cem. is the actual date the comb was erected. As noted earlier, it is always possible that a comb was erected in a later year than the date of death, and in the case of the Stockton combs, a group of five combs were almost certainly erected years after the death dates. But there is not, at present, any reason to suspect that the combs at the Herd-Hurd-Bryant Cem are significantly younger than the dates they bear.

In addition to the 1822 comb in the Herd-Hurd-Bryant Cem., several combs bearing mid-1820’s dates are found in Wilson Cem. (Sparta quad, White Co.) and in Austin (Anderson) Cem. (DeRossett quad, White Co.). An 1822 comb is known to the north in Roaring River Cem. (Okalona quad, Overton Co.), and an 1828 comb is found to the south in Blue Springs Cem. (Viola quad, Warren Co.). Clearly by the mid-1820s the Tennessee comb grave tradition was well established in the White Co. area and strong enough to begin to spread to north and south.

Appendix F is a partial listing of combs with early dates and their locations; their distribution is shown in Figure 6.

Cantrell (1981) meticulously logged the death dates inscribed on over 700 combs in his Caney Fork Valley and Overton County groups. His plots of these data show that the use of comb graves peaked in the 1876-86 decade in White and Van Buren counties, and around 1906 in Overton Co. The plots indicate a rapid decline in the erection of combs in both areas, with some combs still being erected in the Overton Co. area into the 1950s, some three decades longer than in the Caney Fork Valley area.

No collection of dates comparable to Cantrell’s work has been compiled for the present study; however a number of more recent combs were noted. Combs dated 1956 and 1958 were noted in Flat Creek Cem. (Hilham quad, Overton Co.) during the early stages of this project, but have since been removed. Comb graves dated 1967 and 1969 occur in Stockton Cem. (Stockton quad, Fentress Co.), and a pair of sheet metal combs cover the graves of a husband (d. 1983) and wife (d. 2001) in Bear Creek Cem., (Plate 20, Cookeville East quad, Putnam Co.)7. To date, the most recent comb is that of Kathleen Rodgers, who was buried at her home in 2012 (Plate 24, Windle quad, Overton Co.). The two 21st century combs (2001 and 2012) and the separate circumstances leading to their erection have been described in detail by Finch (2013).

Hoping to answer this question, Cantrell (1981) interviewed funeral directors, a monument dealer, other cemetery researchers, a longtime resident of Allred (in the heart of the Overton County comb group), and even a member of the Vaughn family of stonecutters who had quarried gravestones in his younger days. The most common reason cited was to protect the grave from rain. The second most common reason given was to protect the grave from animals, whether domestic or wild. At least one informant said that one purpose for the combs was to make the grave more permanent. Oddly enough, the retired stonecutter said he knew of no reason for combs other than people wanted them.

During the course of the present survey, informal conversations with a few old timers also elicited the same reasons: protection from rain or from animals. With regard to rain, this notion may be supported by the observation of combs sealed with cement in 11 graveyards, by a caulk-like substance in one cemetery, and by metal combs sealed with a tar-like substance in another graveyard. As noted earlier, the normal lapping of one side slab over the other might be for the same reason. However, protecting the grave from rain does not bear up well to logic, inasmuch as there is no real purpose in doing so. Cold logic, of course, cannot be relied upon to explain the reasons for customs surrounding emotional events such as burials.

With regard to protecting the grave from animals, one person remarked that the soil was so rocky that the graves were not very deep, and therefore had to be protected from being dug up by wild animals. This cannot be the general reason, inasmuch as combs are found in many different soil conditions.

An Overton Co. man explaining why he had a box grave erected over his mother in 1954 stated that she requested it, fearing that the graveyard –located in a field—might become neglected and she did not want the cows to walk on her. A second informant reported that as a boy he visited numerous cemeteries with his father who told him that combs were erected to prevent unfenced cattle from walking on graves. “I remember him demonstrating with his foot how a cow's foot would slip off of the slanted side [of a comb].”11 It is certainly true that cattle can severely damage a graveyard by rubbing against headstones to scratch themselves. Worse yet, pigs, rubbing against and rooting underneath gravestones, can and do topple markers and bury them in the mud.

On the other hand, cattle may have been deliberately allowed into some graveyards. According to the White county cemetery book (Pollard, 2003), “In the days before power mowers, the easiest way to keep a cemetery mowed was to allow livestock to graze it. The cover [comb] protected the grave from…trampling.”

While some combs may well have been erected to protect the grave from animals, personal observations show that many a groundhog has found a happy home beneath a comb, and the occasional blacksnake has taken refuge there.

Some combs were erected because they were specifically requested by the decedent or by a family member. Myrtle Webb Judd asked her brother Clio Webb to build a comb for her husband Joe, who died in 1983. Whether or not Joe himself wanted a comb is not known, but he may have, as his parents were buried beneath combs in the same cemetery where he was interred (Bear Creek Cem., Cookeville East quad, Putnam Co.). According to Clio, Myrtle wanted a comb to keep the grave dry. Myrtle also requested a comb for herself, matching that of her husband, and Clio built hers, too, when she died in 2001 (Plate 20) (Finch, 2013)7.

Ball (1999), noting the “desire to protect the burial from the elements or animal disturbance”, concluded that comb graves served the same purpose as gravehouses and other types of grave covers: “Functionally, [combs] are but one of a class of grave marker designed to cover the entire grave which fulfilled an emotional need to provide a level of protection to the remains of the deceased from rain and other factors.”

While agreeing with Ball, I would add that combs make graves more visible and more permanent, less susceptible to being lost (when the cemetery is abandoned) or obliterated (by rain, animals, or vandals). This is an important effect of the comb structures, and was probably the intent or reason behind the erection of some combs. Twenty lone combs were noted in this survey, two in the side yards of homes, one behind a barn, six in pastures/fields and 11 “lost” in thickly wooded areas. Headstones alone might or might not have preserved these grave locations; any or all of these graves could easily have completely disappeared had they not been covered with combs.

None of the above effectively explains why combs became so popular in the comb range. Other forms of grave covers were known and used to some extent. Box graves were more expensive than combs12. Gravehouses, commonly constructed with a wooden frame, did not last as long. Cairn graves and some coffin graves required more stone cutting and dressing labor. All of these forms of grave covers served the same purpose as combs; however, none of these alternate forms of grave covers achieved the enormous popularity of the comb graves.

The very rapid spread of the comb tradition throughout the length of the comb range, documented earlier in this article, suggests that combs may have first become a sort of graveyard “fad,” and later an enduring fashion. They were relatively simple to construct, cheaper than some alternative forms of grave cover, and served a variety of purposes, both emotional and functional, including marking the grave in a more permanent manner than a simple headstone. Combs became fashionable, and like all fashions, this one ran its course. As modern, factory-produced stones of marble and granite became widely available, they became more popular. Concomitantly, the use of combs made by local artisans of local stone declined and nearly died out.

More recently, a single comb grave has been located in the old City Cemetery of Raleigh, N.C. It is made of weakly foliated granitic rock (Plate 25), and it bears the date 1834, making it more than a decade younger than the oldest known combs in Tennessee. To date, there is no evidence for a North Carolina origin for the comb style.

That said, one must admit that emigrants from North Carolina westward into Tennessee undoubtedly carried with them familiarity with the concept of covered graves, such as ledger graves and box graves. Ball (2005, 2008) makes a strong logical case for his supposition that the idea, if not the style, behind comb graves (as well as gravehouses and other forms of grave covers) derives from box and stone table graves popularized in England and Scotland during the 18th century. Several types of grave covers can be seen in the Old Burying Grounds at Beaufort, N.C., including a number of graves covered by comb-shaped structures made of carefully fitted bricks (Plate 26). By construction technique the graves are cairn graves, but the resulting form is distinctly comb-like. None are known to pre-date the Tennessee combs (the four grave covers pictured date from the mid-nineteenth century) and it seems unlikely that these comb-like grave covers inspired the Tennessee combs or vice-versa. The similarity of form is most likely a coincidental repetition of a basic shape.

A number of stone grave covers of triangular form and commonly referred to as "gable shrines" are also known in Ireland14. Three are found in County Kerry: two on the Iveragh Peninsula and one on Illaunloughan Island. The Illaunloughan gable shrine seems to date to the 8th century, and can be seen at https://roaringwaterjournal.com/2023/05/07/illaunloughan/ Two other examples are located at St. Cronan’s Temple in County Clare and are pictured in https://pilgrimagemedievalireland.com/tag/gable-shrine-co-clare/ One of the tomb shrines at St. Cronan’s Temple is thought to cover the grave of St. Cronan himself and date to the 7th century. It has been described as “made of only four pieces of stone, two for the sides, two for the ends, rather like a tent. One end piece is only a half piece—allowing the disciple to put his hand inside and touch the earth where his dear one is buried.”

The Irish tomb shrines have a distinctive look, being much more steeply pitched than the Tennessee combs. Nonetheless, we clearly have a type of Irish comb grave tradition that well predates the Tennessee tradition. Was it the inspiration for the later tradition? The difference in overall appearance, the 1000-year difference in age, and the apparent paucity of examples in Ireland, along with the lack of any “trail” through North Carolina and eastern Tennessee mitigate against --but do not disprove—an Irish origin for the Tennessee comb grave custom.

The similarities between the Tennessee combs and these scattered examples in the UK are most easily attributed to two facts: 1) many cultures evince a desire to protect graves by some means, and 2) a comb-type grave cover is a simple geometric construction that could easily be invented by different peoples at different times, and were.

Based on the evidence currently available, Ball (1999) is correct in stating that the comb grave “likely originated in the early 19th century in the northeastern Highland Rim area of middle Tennessee as a regional adaption of a yet earlier prototype grave covering.” What that earlier prototype was may never be known with certainty.

Regardless of conceptual inspiration, it seems that the comb grave custom as known in the Upland South originated in Tennessee, in the White Co. area, in the 1815-1820 period. The use of combs spread rapidly throughout the main Tennessee range, achieved a popularity that greatly exceeded that of other types of grave covers, and, as discussed below, was later carried into other areas.

The denominationally identified churches include 30 Baptist churches, 18 Methodist, 11 Churches of Christ, 5 Presbyterian, 1 Christian Church, 1 Lutheran church. Six “other” or unidentified churches complete the list. Appendix G is the inventory.) summarizes these findings.

While it is clear the comb grave tradition is not tied to any particular denomination, the birth of the comb fashion coincides closely with the peak of the religious movement known as the Second Great Awakening15. Whether or not the combs are related in any way to this movement remains unclear, however Ball16 feels that “At a minimum, the time lag between the Great Awakening and the earliest known comb graves seems too close for mere coincidence.”

Alabama has a large number of cemeteries with comb graves, 70 of which were verified during the course of this study. In order to compare the Alabama and Tennessee comb grave features, 38 of these cemeteries were visited and photographs were obtained of the great majority of the remaining 32 comb cemeteries. These 70 Alabama comb cemeteries are found in the northern half of the state, in Blount, Cherokee, Cullman, Etowah, Fayette, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Marion, Morgan, Tuscaloosa, Walker and Winston counties. Tuscaloosa and Walker counties seem to be areas of comb concentrations, having 30 and 18 comb cemeteries, respectively, of the total catalogued. Comb counts were made in 34 cemeteries with a total of 338 combs (293 extant combs plus at least 45 ex-combs). If the average of this sample is representative –which is by no means a given-- the total number of combs in the 70 comb cemeteries should be in the 690-700 range. However, these 70 graveyards represent less than a third of the comb cemeteries known in Alabama: cemetery researcher Dr. Ray Hutchison17 has documented 231 comb cemeteries containing 1251 combs. Furthermore, Hutchison has found comb cemeteries in two additional counties, Bibb and Lawrence.

It is assumed that a comb grave cover is erected at the time of the interment or not long after, so that the recorded death year is, in most cases, the year the comb was erected. Death year dates were collected from 181 combs, ranging from 1840 to 1932, with dates in the 1870s, ‘80s, and ‘90s accounting for 70% of all dates. Brown (2004) also found that “most Alabama combs date between the 1840s and World War I.”

The Gravlee-Nall Cem. in Fayette Co. is notable for a row of six virtually identical combs, constructed of finely cut grey limestone and marked with small flat granite headstones dated 1920, 1930, 1930, 1978, 1980 and 1984. The uniformity of the combs and headstones suggests that all six of these combs were erected at the same time, 1984 or later. A Gravlee family member confirmed that his grandfather, being an admirer of the comb grave tradition, had all six of these combs erected, at the same time, over the graves of these family members, some of whom had been deceased for many decades18. Thus the Gravlee-Nall graveyard shows that there are exceptions to the assumption that dates of death indicate the dates of comb construction. Furthermore, Gravlee-Nall, though something of an outlier in time, shows that the comb grave tradition did not completely die out in Alabama in the first half of the 20th century.

The Cargile Cem. (Jackson Co.), containing three limestone combs, may be the northernmost Alabama comb cemetery. It is the closest known Alabama comb cemetery to the main Tennessee comb range, lying just 23 miles from the southernmost cemetery in the main Tennessee range, the Perkins Cem. (Winchester quad, Franklin Co.).

The Roberts family cemetery in Morgan county contains several combs and is of particular interest as it is reported19 that the Roberts family moved to Alabama from White Co., Tennessee. It would appear they brought their burial customs with them, but inasmuch as the oldest dated comb in this graveyard is inscribed 1882, the Roberts clearly were not the first to bring comb graves to Alabama.

Of the 70 Alabama comb cemeteries recorded for this study, over 40% (30) are found in the northern half of Tuscaloosa Co., where sandstone suitable for comb slabs occurs. In addition to this geologic influence, it is also interesting to note that local historians say that this portion of the county was settled by emigrants from Tennessee20.

As in Tennessee, the preferred stone for comb construction in Alabama was sandstone. The Hartselle Formation, present in the Alabama comb grave region (the type section is near the town of Hartselle, whence the name), is predominantly quartz sandstone, and probably was the source of some comb slabs. Another unit quarried for sandstone in Alabama is the Pottsville Formation of Pennsylvanian age21. The Pottsville contains sandstone of dimension stone quality, despite a tendency to spall upon weathering. It was quarried for the original state capitol in Tuscaloosa and for stone used in locks and dams on the Black Warrior River, and for some of the early tombstones in Tuscaloosa’s Greenwood Cemetery22. A comparison of the locations of the 70 comb cemeteries verified in this study with the geologic map of Alabama shows that the majority (46) are located on outcrops of the Pottsville Fm. or, if actually sited on other stratigraphic units, then very close to Pottsville outcrops (12). Only a single comb cemetery was found to be located on the Hartselle, with one additional cemetery being located close to Hartselle outcrops. Considering the transportation difficulties during the era of comb erection, it is only reasonable to assume that local availability determined which unit supplied the sandstone slabs used in the comb graveyards.

Regarding the geographic range of the Alabama comb cemeteries, all but two of the Alabama counties in which combs have been reported lie partially or wholly within the Cumberland Plateau physiographic province. (The exceptions are Cherokee Co., which lies in the Valley and Ridge province, and Bibb Co., which lies just outside but near the southern edge of the Cumberland Plateau province.) In Alabama the Cumberland Plateau is more dissected and discontinuous than in Tennessee, and Pottsville (and to a much lesser degree, Hartselle) outcrops are found over a broad region. If, as seems certain, these units supplied most of the comb slabs, this may explain why combs are found not in a linear belt as in Tennessee, but scattered over an irregular geographic area as broad from east to west as from north to south. Nonetheless, the Alabama comb range appears to be controlled by the distribution of suitable sandstone outcrops, just as in Tennessee.

Taking a multistate viewpoint, it could be argued that the Alabama comb cemeteries are in fact a continuation of the Tennessee comb range. However, there is a gap --albeit not a large one-- between the two collections of combs, both geographically and, it would seem, temporally. The use of comb graves in Alabama developed later than in Tennessee.

In Arkansas, comb graves have been documented in at least 18 cemeteries in 11 different counties, with a total of something over 50 combs23. Almost all of these comb cemeteries are found in the Ozark Mountains region (northwest and north-central Arkansas), in Benton, Boone, Cleburne, Crawford, Franklin, Fulton, Newton, Searcy and Sharp counties. Only two comb cemeteries are known to lie outside of the Ozarks, one in Perry Co. in the central part of the state and one in Pike Co. in southwest Arkansas. Seven of the Ozark cemeteries were visited during the field work for this study. Most of the observed combs did not feature dates, but those that did ranged from 1855 to 1883.

Again, most combs were made of sandstone slabs, but a few were of limestone, including very finely dressed limestone (coarsely crystalline pink limestone, likely sold as marble) combs in Holmes Cem. in Boone Co.

The known comb grave cemeteries in Arkansas seem to be scattered over a wider area than the relatively narrow geographic belt containing the Tennessee combs. This may indicate that more comb grave cemeteries remain to be discovered in Arkansas. One might also infer from this distribution that the Arkansas combs result from the “Tennessee diaspora” described by Jordan-Bychkov (2003). One of the eight combs in Holmes Cem. covers the grave of a woman originally from Tennessee24 and Tennesseans from Overton Co. (including stonemasons from the Allred and Norris families) are known to have migrated into the Ozark region of northwest Arkansas25. In her book on burial customs of the Arkansas Ozarks, Burnett (2014) states that “older burials were protected by a variety of grave coverings, their styles [her list includes comb graves] having all been traced back to Tennessee.”

Combs are known from eight Kentucky cemeteries, one of which, Taylor Grove Cem., is included in the northernmost end of the main Tennessee comb grave range. Four of the other seven comb cemeteries visited during fieldwork for this study –Redbird, Steely, and Canada Church cemeteries (Wofford quad, Whitley Co.) and Ballou-Worley Cem. (Cumberland Falls quad, McCreary Co.)-- all lie 40 to 45 miles northeast of the easternmost Tennessee comb cemetery. Redbird Cem. was reported by Richmond (1998) and Ball (1999); it contains six combs, made of sandstone (as would be expected, considering the geology of the Cumberland Mountains). Three of the six combs are dated: 1862, 1863, and 1922(?). Nearby Steely Cem. once had three combs, now dismantled, and Canada Church cemetery has three combs. Ballou-Worley Cem. contains a single sandstone comb dated 1860.

The remaining three Kentucky comb cemeteries are found in western Kentucky, between Hopkinsville and Lake Barkley, well to the west of the main Tennessee comb range. Lander Cem., in westernmost Christian Co., holds four combs, three made of calcarenite (limestone of sand-sized grains) composed of fossil bits and ooids, and one made of white marble. The talented stonecutter who erected these combs did excellent work in dressing and shaping the side slabs, most of which, if not all, feature beveled upper edges so that they meet neatly at the crest of the comb. Unfortunately, these combs are not in good condition, for two reasons: the calcarenite tends to disaggregate and split apart as it weathers; furthermore, it appears that no gable stones were used to support the side slabs, leading to a tendency for the side slabs to spread and collapse with time. Three of these combs are dated: 1857, 1860 and 1860. Sinking Fork Cem., located a little east of Lander, holds a single comb, of the same type of stone and style as the Lander combs, and probably by the same stonecutter.

Just a few miles to the west, across the line in Trigg Co., lies Wall Cem., which has a single comb, made in the same style as the Lander and Sinking Fork combs, of the same calcarenite, and likely by the same stonecutter. In addition to deterioration of the comb by weathering, its headstone has recently (since 2012) been broken into several pieces, possibly by vandals. This comb is especially interesting due to its date, 1847. It has been demonstrated earlier in this paper that the practice of erecting combs over graves spread very rapidly throughout the main Tennessee comb range; this comb in Wall Cemetery shows that the practice did not require many years to be carried beyond its main range.

In West Virginia, combs constructed with roofing metal have been documented in two cemeteries in northern Mingo Co., not far from the Kentucky border. Newsome Ridge Cem., sited on a high and remote ridge, is a graveyard in which traditional grave customs are still strongly maintained. Five relatively recent combs made of corrugated roofing “tin” are found here. Four bear dates: 1937, 1947, 1948, and 1952, long post-dating the majority of the Tennessee combs. In addition to these five metal combs, nine gravehouses—including a new one in the process of being erected in Sept. 2014—were noted. Annually, on the third Sunday in August, local folk hold a cemetery decoration day that is attended by hundreds. This meeting is called the “Reunion” or “Basket Meeting” because participants bring baskets of food to be shared in a communal “dinner on the ground”, laid out on a long buffet table in the cemetery’s pavilion26.

In nearby Rose Town, at the Rose and Brewer Cem., a metal comb lies somewhat downhill and just outside of the graveyard proper. It is also 90 degrees out of alignment with the other graves (which run east-west, facing east). The corrugated “tin” comb is intact, but has been removed from the grave to which it once belonged, and discarded, possibly to make mowing easier. A local informant stated that there were formerly at least two combs in this cemetery.

No connection between the West Virginia combs and the Tennessee combs has been established. However, the use of “Tennessee” as a woman’s given name in another nearby Newsome family cemetery hints that a connection may exist.

Two Texas cemeteries are known to feature comb graves. Shiloh Cem., in Denton Co., contains an elegant marble comb (Plate 27), the ends of which are closed by large, matching head- and footstones much in the same manner as the truncated triangle combs of Overton Co., Tennessee. The name on this comb is Nancy Yeats and the date of death is 1910. How this lone comb came to be erected here is not known, but several possible connections with Tennessee exist. Although Nancy Yeats and her husband Dr. T. A. Ball came to Denton Co. from Missouri, Nancy was born in Tennessee; it is not impossible that Yeats might be the same surname spelled Yates in several comb cemeteries in Tennessee (e.g., Cold Hollow and Gravel Hill cemeteries in the Bald Knob quad, Van Buren Co.). Furthermore, the county and town of Denton were named for John B. Denton, a Methodist-Episcopal preacher and Indian fighter who was born in White Co., Tennessee in 1806. However, Denton was orphaned at age eight and moved with his adopted family to Arkansas around the same time the comb grave style was nascent in Tennessee. Hence it seems unlikely that Denton took any knowledge of comb graves with him when he left his natal state. In Arkansas he became a preacher, and in this profession would certainly have become familiar with burial customs, including, perhaps, comb graves. Yet if Denton brought the idea of comb graves from Arkansas to Texas, there should be other combs in this area, for Denton died in 1841, long before Nancy Yeats arrived around 1865. Other Dentons from White county emigrated to Texas around 187027 and the role of Tennesseans in Texas history is well known. It seems likely that the Nancy Yeats comb has Tennessee origins, whether through Yeats herself, John B. Denton or someone else.

Mississippi has at least one cemetery that features comb graves. Pickle Cem., in Monroe Co., has four sheet metal combs ranging in age from 1946 to 199130. Thornton31 describes these combs as grave shelters and adds that he remembers others from his youth. It would not be surprising if other comb cemeteries still exist in Mississippi.

In Louisiana, one comb is found in the Old Bellwood Cem. (Natchitoches parish). It is a limestone comb for a child who died in 187832.

The lone North Carolina comb, dated 1834, in the City Cemetery of Raleigh (Wake Co.) has already been described.

Combs are known from a single cemetery in Georgia. In 2023, in western Spalding Co., as a property was being subdivided for development, a nearly forgotten graveyard known locally as Old Salem Cemetery was encountered. Old Salem contains approximately 55 graves, the great majority of which are marked only by uninscribed field stones. But there are also a number of crudely constructed box graves, plus two smallish combs that probably cover children’s graves. The combs are each covered with a pair of slabs made from foliated metamorphic rock. These side slabs are somewhat rough-hewn, but clearly each pair was originally leaned together in the form of a gable roof. Unfortunately, the slabs were not supported by gable stones, nor was any supporting fill used, so both combs have suffered some degree of collapse though time. These combs are undated, and in fact, little is known about the age of Old Salem Cem. Nonetheless, with this discovery, Georgia joined the ranks of states known to have comb graves33.

In Missouri, two cemeteries are known to feature comb graves34. Though located in Missouri, these two comb cemeteries lie not far north of the state line with Arkansas and are part of the same Ozark cultural area as northern Arkansas, in which comb graves were a part of the cultural heritage brought in by immigrants from Tennessee.

In the very SW corner of Missouri, in McDonald Co., within the town of Noel, just 3-4 miles north of the line with Arkansas, lies Noel Cem., which features two comb graves. Further to the east, in Ozark Co. and just a few miles north of the state line lies Souder Cem. with four uninscribed --no dates, no names-- combs, along with what may be a collapsed former comb. A letter to the editor of "The Ozarks Mountaineer" (Oct. 1988 issue) suggests that at least one comb grave exists in Jasper Co., Mo.

While never officially a part of the Confederacy, southern Missouri is culturally part of the "Upland South" (Jordan-Bychkov, 2003), and received many settlers from Tennessee in the 1850-1880 period.

Eastern Oklahoma also lies within the cultural region of the Upland South (Jordan-Bychkov, 2003) and comb graves arrived here prior to statehood. At least three comb graves, extant in 2016, are documented by photographs in Old Cache Cem., near Keota, in Haskell Co. The combs seen in the images are very typical combs, and could easily pass for combs in a Tennessee graveyard. The stone slabs have the appearance of being sandstone, though it is difficult to be certain from photographs. One of the combs covers the grave of a child named Sarah Jackson and bears a date of death that appears to be 1891 (or possibly 1881).

According to local lore, the combs in Old Cache Cem. cover Native American graves. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to ascertain whether or not this fervently held belief is correct, the fact that the original land for the cemetery was donated by the Choctaw Nation makes this local history more plausible than it might otherwise seem. Furthermore, Jackson is a common Choctaw surname. The Choctaws were one of the Five Tribes (often referred to as the “Five Civilized Tribes”) that had adopted Anglo names and ways early in the 19th century. Further research would be needed to demonstrate that the combs at Old Cache Cem. are Native American graves, but the possibility is intriguing35.

In Muskogee Co., about 30 miles west from Old Cache is the 1889 grave of Belle Starr, notorious as the "Outlaw Queen." Photographs of her gravesite, which may be seen on the internet, show that her grave is marked by a structure that looks like a box grave made of cut stones and topped by a stone slab comb. This monument is very like the transitional comb structures found in Holmes Cem. in Arkansas (and described later in this paper).

On the basis of the Old Cache combs and the Belle Starr grave, it seems likely that a search of eastern Oklahoma traditional cemeteries would turn up more comb graves.

This survey of combs outside of Tennessee, while admittedly incomplete, indicates that Tennessee has by far and away a greater number of comb cemeteries and combs than any other state. The oldest known combs are also found in Tennessee. With the exceptions of the single North Carolina comb, the ten Kentucky combs lying to the east of the Tennessee comb range, the two combs in Georgia and the six combs in West Virginia, all the other extant non-Tennessee combs are found westward or southward of the main Tennessee comb range. Westward, of course, was the general direction of historic migration. From this distribution pattern of numbers of comb cemeteries and combs, dates, and apparent westward spread, it is reasonable to infer that the comb tradition originated in Tennessee.

It should be noted here that the dispersion of the comb grave tradition from Tennessee into other Southern states is but one facet of a larger and more complex cultural transfer. Jordan-Bychkov (2003) defined the Upland South not only by its geography, physiography and agricultural style, but by a specific material culture. He argues persuasively that the Upland South culture first came to full flower in central Tennessee in the early 19th-century and was carried to the rest of the region by the “Tennessee diaspora.” The suite of cultural features Jordan-Bychkov found diagnostic of the Upland South includes graveyards and mortuary customs, and in particular, gravehouses (which he called “gravesheds”). While he did not mention comb graves per se, he was definitely aware of combs (as indicated by his reference to Finch, 1982). Possibly he considered combs a subclass of gravehouse (as did Ball in his 1977 paper). In the light of this general spread of material culture and customs from Tennessee westward and southward, the findings presented in the present paper regarding the origin and spread of the comb grave tradition are not unexpected.

The popularity and variety of cement grave covers in the Fairburn and Campbellton cemeteries, the use of brick sub-structures, and the failure to mimic the side slabs or gable stones in those structures that were comb-like in form all point toward the conclusion37 that these grave covers were not built by people aware of the comb grave style. Those grave covers that were comb-like were at best “coincidental combs”, resulting from the independent use of a very basic geometric form in the construction of a cement grave cover.

In Sussex County, just north of the state line with Maryland, lies Bethel M. E. Church where the original church building was erected in 1841. At Bethel the writers of Delaware: A Guide to the First State (a Federal Writers Project publication issued in 1938) found “several old graves with shingle roofs…. ….examples of the once-popular local custom of placing a small pitched roof close over a grave to keep off the rain”. According to Zebley (1947), “in the old graveyard a few roofed-over graves can be seen, one of the few places in Delaware where any of these graves remain. These roofs are A shaped with the gables closed in, rest directly on the ground with the entire frame-work covered with shingles.” Zebley provides a photograph39 showing two combs in Bethel cemetery; the construction of the comb in the foreground of Zebley’s photo clearly fits the definition of comb grave, i.e., a grave cover in the form of a gable roof set directly on the ground over the length of an in-ground burial. As illustrated by the varied materials used for the construction of the Tennessee combs, it is the form, not the materials used, by which a comb may be defined. The Delaware combs were naturally made of wood inasmuch as stone suitable for quarrying is scarce or non-existent in this region.

Zebley goes on to state that “in the private graveyard on the farm of Ira West….there are several graves over which roofs have been built…. The most recent of these were over the graves of John C. West who died in 1858 and Mahala West who died in 1852.” In addition, he mentions that there “is one roofed-over grave” at King’s M.E. Church, where the first church building was erected in 1842. A third author, Pepper (1976), writes that “an old graveyard in back of Millard Johnson’s home near Bayard had some graves with a roof on top of each one. The A-shaped roofs were made of cedar shingles pointed on top exactly like a house roof, and each one covered an entire grave.” A 1947 photograph shows a comb over an 1891 grave near Bayard; this comb, like the Bethel and West combs has not survived to the present.

Immediately south of Sussex Co. lies Wicomico Co., Maryland, where Jacob (1971) reported that “it was the custom in the eastern section of Wicomico for many years to build a roof over a new grave. The roof was built on an ‘A’ frame, the peak about thirty inches high, with the structure covering the entire grave.” According to Jacob, only one of these grave roofs remained in 1971.

It is notable that the sources quoted above referred to the grave covers as “roofs”. The term “comb grave” was not used by these writers, and it seems likely that the term was not used locally. The overall number and time range of the Delmarva combs is unknown at present. The only dates currently known for Delaware combs are 1852, 1858 and 1891. An intriguing question is how long could wooden combs have survived? Pepper (1976) mentions “cedar” shingles, but a shingle-making industry using both cedar and bald cypress --the latter a very durable, rot-resistant wood-- was formerly important in Sussex county, and combs constructed of cypress would indeed have been long-lived for wooden structures. Although a number of combs still existed in the late 1930s and 1940s, and at least one as late as 1971, so far as is known, no Delaware or Maryland combs have survived to the present, presumably due to the ultimate perishability of the wood of which they were constructed.

What little is known of the dates for the Delmarva combs suggests that they post-date the earliest Tennessee combs, and therefore were not the source for the idea of combs in Tennessee. Furthermore, while it is unknown how many Delmarva graveyards once featured combs, it seems clear from the small number reported that the custom never became very widespread or strongly entrenched here, and therefore was less likely to have been exported. On the other hand, by reviewing census reports Slavens has found that dozens of residents from the Delmarva Peninsula emigrated to Tennessee. For example, Thomas West, born 1760 in the Delmarva region settled in DeKalb Co., Tennessee in 1804. The main Tennessee comb range extends into DeKalb Co. The possibility of a cultural exchange involving mortuary customs—either from Delaware to Tennessee or a cultural backflow from Tennessee to Delaware--- cannot be ruled out by the information currently in hand. Alternatively, the Delaware combs may simply have resulted from an independent solution to the problem of covering and protecting the graves of loved ones, employing one of the simplest –both in geometric form and in construction-- types of grave covers. It is a pity that neither the combs nor custom survived on Delmarva to present times.

For a more complete discussion of the Delmarva roofed graves, see Slavens (2020).

Concurrently with the “truncated triangle” combs, the Vaughn family of quarrymen also produced box graves consisting of four large sandstone slabs, held upright against each other by long iron cross bolts, and topped by an even larger flat-lying sandstone slab. The distinctive feature of these massive boxes was the necked discoid headstone that was integral with, and an extension to, the upright slab at the head end of the grave. Judging from two graves in Beaty Cem. (Moodyville quad, Pickett Co.), a few discerning comb customers wanted the best of both styles: the “truncated triangle” plus a necked discoid (Plate 29).

Zip’s comb is made of sandstone slabs from a quarry in Rhea Co. The stones were cut, Zip’s name engraved, and the comb erected by a close friend of Zip’s master. Inasmuch as Zip’s comb was erected in 2013, the earlier statement regarding the Kathleen Rodger’s 2012 comb as being the most recent comb must be revised as the most recent comb for a human being.

A third pet comb exists in a backyard in Monterey (Putnam Co.), where it was constructed several years ago over the grave of a pet dog. The gentleman who erected it formerly worked in kitchen counter installation and had some spare slabs of stone. Although he was unfamiliar with the term “comb grave,” he most likely was inspired by combs seen in local cemeteries.

While combs over pet graves are a rarity, they are nonetheless legitimate combs. They are erected out of affection for and in tribute to the departed friends, just as regular combs have been erected.

The reasons for the loss of combs are numerous. Cantrell (1981) notes that some cemetery committee members feel combs do not fit in well with “well-ordered rows” of modern headstones, that they are a “hindrance to the proper upkeep of a cemetery”, that they are “snake harbors,” and that they “are being removed to make graveyard cleaning easier.” In the mid-1960s the trustees of Dodson Chapel cemetery decided to have all the comb grave covers removed (along with a couple of box graves) to "modernize" the cemetery. Ball (1997) comments “even markers made of stone are not impervious to the long term deteriorating effects of wind, rain, and freezing weather or destruction by unthinking (or uncaring) individuals bent on vandalism.”

During the present study the following reasons for damage to or destruction of combs were catalogued:

To respect the wishes of both the departed and of their loved ones who memorialized them with combs, we should preserve the remaining combs. The combs provide an interesting glimpse of a nearly bygone funerary custom, one that apparently is original with Tennesseans. In the words of Lynwood Montell, a well known folklorist, “these traditional prismatic grave structures more than any other single cultural feature lend uniqueness to the folk cemeteries in the Upper Cumberland” (Montell, 1993). The comb graves of Tennessee, and other states as well, constitute an interesting and valuable part of our material cultural heritage and should be cherished.

Tennessee combs are found in a geographic belt that parallels the western escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau from Winchester northward to just across the state line into Kentucky. The majority of combs are found in small cemeteries on the Eastern Highland Rim, but combs are also found on the Hartselle Bench and on the western portions of the Cumberland Plateau itself. This geographic distribution strongly correlates with the outcrop trace of the Hartselle Formation along the western flank of the Plateau and in erosional outliers of the Plateau. Evidently, the presence of appropriate sandstone in the Hartselle Formation exerted a major control on the use of combs to cover graves.

Within the main comb range there are two notable local concentrations of comb graves in the Caney Fork Valley (White and northern Van Buren counties) and in Overton Co.

Although admittedly incomplete, the data presented in this paper, augmented with anecdotal information, point toward the conclusion that the style of covered graves known as comb graves originated in Tennessee, in the White Co. area, in the 1815-1820 period (possibly slightly earlier, certainly no later). From Tennessee, the comb style and custom was carried, mainly westward and southward, into other states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Missouri and Oklahoma, and also into Kentucky, West Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia. The relationship, if any, between the Tennessee comb tradition and the former wooden combs of the Delmarva Peninsula remains at present enigmatic.

Historic picture postcards show that at least a few Native American Spirit Houses were, by form and construction, combs; however, it seems probable that these grave covers were unrelated to the Tennessee comb grave tradition.

More definitively documented by the data, the comb style spread rapidly throughout the full length of its main Tennessee range by the late 1830s. The style achieved its greatest popularity during the latter half of the 19th century and was still commonly used, especially in Overton Co., up through the 1930s. By the 1950s the practice of erecting combs over graves had nearly been abandoned, with a few rare exceptions. Nonetheless, the custom has survived into the 21st century, the most recent two combs for human interments being erected in 2001 and 2012.

Combs serve the same functional purposes as any other form of grave cover, primarily to offer some protection to the grave from the elements and, to some extent, from animals. The erection of a comb over the grave of a loved one no doubt also helped fulfill emotional needs, showing that the deceased was cared for. Combs also serve to make graves more permanent, less likely to disappear when graveyards cease to be kept up.

During the course of this study comb graves were documented in 521 Tennessee cemeteries; however, the actual number of comb cemeteries is certainly higher. As of 2025 there were 3669 extant comb graves known in Tennessee, far more than any other state. Unfortunately, combs are being dismantled or destroyed for a variety of reasons, none of them very good. At least 46 former comb cemeteries are known within the main Tennessee comb grave range; of these, 20 have lost their combs since this survey was initiated in the mid-1970s.

In recent years, combs have been erected over at least three pet graves.

Comb graves, an original Tennessee folk custom, represent an unusual and charming part of Tennessee’s material cultural heritage. Comb graves should be appreciated and conserved, yea even cherished.

Nameless, forgotten, her home long abandoned and now almost entirely obliterated, the short existence of the Gore infant is still memorialized 123 years after her death. Indeed, the fine-grained, quartz-cemented Hartselle sandstone will easily endure long after marble has weathered to illegibility; the sandstone will likely outlast granite. Barring its destruction by a falling tree or vandals, this comb should easily attest to her memory for several centuries more. Hikers wandering through the woods will readily see her grave long after the house site is completely unrecognizable. This solitary comb in the wilderness bears witness to the remarkable permanence of the Hartselle sandstone comb graves.

2Rector Cemetery is transected by the Kentucky-Tennessee border, and whether this comb lies in Tennessee or Kentucky or is actually bisected by the line has not been determined.

3Nearly 50 cemeteries could not be located. Around 11 seem to have been moved: possibly as many as seven for the impoundment of Cordell Hull reservoir, two for I-24, one for mining activities near Elmwood, and one for the building of a home. Three apparently were bulldozed into oblivion; one or two likely were plowed under; and 30+ others have simply disappeared through time, weathering, erosion and neglect.

4When sandstone slabs are pried out of the quarry, they tend naturally to break across the bedding at right angles. To cut a beveled edge would likely be difficult in the thin beds preferred for comb slabs, though an example can be seen in Beaty Cem., Moodyville quad, Pickett Co.

5White (2002), who studied a variety of types of grave covers --including combs-- concluded that the "period of use, [sic] for comb covers seems to be from about 1840 to 1900." To draw this conclusion, he had to exclude from his data set the dates of the bolted combs, which he referred to as "a newer version of comb covers". Thus he called them combs, and mentioned their having "death dates well into the 1900s" and "from 1900 to 1950", yet excluded them from consideration in determining the temporal range for the use of comb covers. Cantrell (1981) included these bolted combs in his set of comb grave dates, a fact White mentioned while failing to explain his own reason(s) for excluding them. He stated that this "newer version" was centered on Falling Spring [sic] Cemetery and "spread to only a few other cemeteries". In truth, White's sample was too small to justify these conclusions. He documented various grave covers in 288 cemeteries (many outside the known comb grave range); how many of these 288 cemeteries contained comb covers he did not report, but he did note a total of 311 comb graves. In actuality, the bolted combs are widespread in Overton Co. and are found as far west as central Putnam Co. White's writings on this particular subject are confusing, but it appears that he does not believe the "newer version" of comb covers are legitimate comb graves. While they involve taller than usual head- and footstones, the bolted combs have the same basic shape as all combs; they are made of the Hartselle sandstone as are most combs; and they serve the same purpose(s) as other combs. The principal difference is the iron rod support system in place of gable stones. The bolted combs represent a local variant in comb construction style, developed at a later date than the early combs in the White Co. area, but they are indeed legitimate comb graves, and their time range is part of the over all comb grave time range.

6A few miles to the south, Christian Cem. (Silver Point quad, Putnam Co.) features another grave covered with Chattanooga Shale slabs. The head half of this grave is covered by two slabs leaned together like a comb, but the foot half at present appears to have only a single flat-lying slab. It is unclear whether or not this grave cover was originally constructed as a comb.

7Both these 5-Vee roofing metal combs were constructed by Clio Webb at the request of his sister, Myrtle Webb Judd. The first was constructed and emplaced over the grave of Myrtle’s husband, Joe Judd, who died in 1983. When interviewed on this subject in 2012, Clio stated that Myrtle wanted a comb “to keep the grave dry”. The metal comb constructed by Clio closely matched the metal combs that once covered Joe’s parents (which Clio did not construct) nearby in the same cemetery (but which have since been removed). When Myrtle died in 2001, Clio constructed a second comb, matching that of Joe’s, again in accordance with his sister’s wishes. This was the first comb to be constructed in the 21st century, (and one of only two known thus far).

As of 2012, Clio was still maintaining these two combs when they needed repair; a few years later, as his health declined, Clio apparently was not able to continue to look after them. Clio died in Feb. 2021, and as of Dec. 2022 both combs had deteriorated, with Myrtle’s comb being completely collapsed. No doubt the remains of these combs will be removed from Bear Creek Cem. in the not-too-distant future, and the number of 21st century comb graves will be reduced to a single example.

8The stratigraphic generalizations stated in this paper are based on data from 7 ½ minute geologic quadrangle maps published by the Division of Geology, Tennessee Dept. of Environment and Conservation.

9Kathy Stockton Williams, personal communication, January 2014.

10Both the author of this paper and Michael McNerney originally thought this stone was cut at a date later than 1817. McNerney, who has studied the evolution and spread of the necked discoid style, estimated that this headstone was carved sometime within the years 1825-1835. (McNerney, personal communications, Mar. 2013 and Jan. 2014). We now doubt this earlier interpretation.

11Cliff Owens, personal communication, Apr. 2014.

12Cantrell, 1981, reported that in the 1930’s a comb set cost $30, whereas a box set cost $60.

13Emma Herbert-Davies, University of Leeds, sent a description and images of the Otley comb; personal communications, Jan. 2016.

14Dr. Ray Hutchison, Prof. of Urban and Regional Studies, Univ. of Wisconsin, Green Bay, alerted me to the existence of these grave structures, personal communication, Jan. 2016.

15This time relationship was first called to my attention by graveyard enthusiast Dr. Ray Hutchison.

16Donald B. Ball, personal communication, Mar. 2014.

17Dr. Ray Hutchison, personal communication, May 2021.

18Dr. Ray Hutchison, personal communication, May 2021.

19 http://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/25835/Roberts-family-cemetery/photo#view-photo=15137701

20James Ezell, P.E., personal communications, May 2016.

21Dr. Eugene M. Wilson, Prof. of Geography, Univ. of South Alabama, suggested that sandstone from the Pottsville Formation of Pennsylvanian age might also be a source of comb slabs. Personal communications, Oct. 1981, Apr. 2014.

22James Ezell, P.E., personal communications, May 2016.

23I am much indebted to cemetery researcher and author Abby Burnett for sharing her knowledge of Arkansas comb cemeteries and guiding me to see several of them.

24John Waggoner, Jr., personal communication, Mar. 2014.

25Michael McNerney, personal communications, May 2013.

26Dr. Alan Jabbour, personal communications, Sept. 2014 and Apr. 2015.

27Beth Moore Farmer (a Denton descendant), personal communication, Feb. 2014.

28The late Dr. Terry G. Jordan, personal communication, Aug. 1981.

29John Waggoner, Jr., personal communication, Nov. 2014.

30John Waggoner, Jr., personal communication, Feb. 2014.

31Terry Thornton, http://hillcountryhogsblog.blogspot.com/2010/04/grave-shelters.html

32John Waggoner, Jr., personal communication, Jan. 2014.

33I thank Dennis and Mike Scott of the organization Monumental Preservation for informing me of the presence of these two comb graves in Old Salem Cemetery.

34Many thanks to Abby Burnett for seeking out these Missouri cemeteries and providing photographic proof of Missouri comb graves.

35My thanks to Dagmar Anne Cole of Ft. Worth, TX, for calling the combs in Old Cache Cemetery to my attention, and to Jerry Smith of Cartersville, OK, for providing images.

36Marion O. Smith, personal communication, Apr. 2014.

37I am indebted to Steven A. Hurd, Ray Hutchison and John Waggoner, Jr. for insightful comments regarding these debatable comb graves in the Campbellton Baptist Cemetery.

38Chris Slavens, personal communications, Sept. 2016; also Slavens (2017, 2020).

39Zebley (1947), p. 349; see also the Zebley Collection Churches of Delaware, Delaware Public Archives for a better image.

40I am grateful to John Waggoner, Jr. for making his collection of postcards picturing Spirit Houses available to me.

41In the Allred area a truncated triangle comb covers an 1847 grave in Shiloh Cem., several dated in the 1850s are known, and a 1963 date occurs on a truncated triangle comb in Cub Cem. (all in Crawford quad, Overton Co.).

42Scott Cem. (Walker Co., Alabama) contained 51 combs when visited in May 2019. Many, perhaps the majority, are earth-filled combs. Many are also in a state of partial to complete collapse. Although no data were collected to document the % of the total that are earth-filled, nor any data collected to document a positive correlation between earth-filled and collapsed combs, general observation and photography left a strong impression that earth-fill leads to collapse. Many of the collapsed combs have clearly spread laterally, the side slabs moving away from and at right angles to the center line of the comb. As they spread apart, the slabs rotate to angles much flatter (lower) than when the comb was originally set up, with a gap between the upper edges of the slabs that commonly exceeds a foot. It seems likely that the slabs have actually been pushed apart by expansion of the earth fill during many years of freeze/thaw cycles. If this interpretation is correct, then the earth-filled combs contain within themselves the seeds of their own destruction.

43Dr. Joseph C. Douglas, personal communication, Mar. 2014.

Ball, Donald B., 1997, Types of Early Grave Decoration in Middle Tennessee: Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin, v. LVIII, n. 3, p. 117-127.

Ball, Donald B., 1999, Comments on the Distribution and Chronology of Comb Graves in the Upland South: Ohio Valley Historical Archaeology, v. 14, p. 58-66.

Ball, Donald B., 2005, Further Observations on Gravehouse Origins in the Upland South: Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin, v. LXI, n. 2, p. 17-30.

Ball, Donald B., 2008, An Alternate Hypothesis on the Origin of Upland South Gravehouses: Ohio Valley Historical Archaeology, v. 23, p. 101-118.

Ball, Donald B., John C. Waggoner and Richard C. Finch, 2016, Note on an Unusual Double Comb Grave in Jackson County, Tennessee: Ohio Valley Historical Archaeology, v. 26, p. 142-144.

Brown, Ian W., 2004, Some Grave Houses in West-central Alabama: AGS Quarterly, Bulletin of the Association for Gravestone Studies, v. 28, n. 2, p. 14-15.

Burnett, Abby. 2014. Gone to the Grave: Burial Customs of the Arkansas Ozarks, 1850-1950: The University Press of Mississippi, 327 p.

Cantrell, Brent, 1981, Traditional Grave Structures on the Eastern Highland Rim: Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin, v. XLVII, n. 3, p. 93-103.

Crissman, James K., 1994, Death and Dying in Central Appalachia: Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 247 p.

Federal Writers’ Project, 1938, Delaware: A Guide to the First State, Compiled and Written by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration: The Viking Press, New York, 549 p.

Finch, Richard C., 1982, Unique Grave Houses in Tennessee: Monterey, TN, The Standing Stone Press, 4th year, n. 4, Spring 1982, p. 1-3.

Finch, Richard C., 2004, Ashes to Ashes, in Birdwell, Michael E. and Dickinson, W. Calvin, 2004, Rural Life and Culture in the Upper Cumberland: Lexington, KY, The University Press of Kentucky, p. 66-72

Finch, Richard C., 2013, Tennessee Comb Grave Tradition Survives into the 21st Century: Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin, v. LXIX, n. 1 (Spring 2013), p.17-24.

Jacob, John E., 1971, Graveyards and Gravestones of Wicomico: Salisbury, MD, Salisbury Advertiser, 131 p.

Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G., 2003, The Upland South: Santa Fe, NM, Center for American Places, 121 p.

McNerney, Michael J., 2017, A Shape in Time and Space: The Migration of the Necked Discoid Gravemarker: Tuscaloosa, AL, Borgo Publishing, 246 p.

Montell, William Lynwood, 1993, Upper Cumberland Country: The University Press of Mississippi, Print-on-Demand Edition, 187 p.

Oxford English Dictionary, The Compact Edition, Vol. 1 A-O, 1971: New York, Oxford University Press, p. 472.

Pepper, Dorothy W., 1976, Folklore of Sussex County, Delaware: Sussex County Bicentennial Committee, (no publisher given), 116 p.

Pollard, Geraldine Elrod, ed., 2003, The Fred Clark Book of Cemeteries of White County, Tennessee, v I and II: Published by The White County Genealogical – Historical Society, 564 p. and 524 p.

Richmond, Michael D., 1998, An Archeological Survey of the Proposed Lake Cumberland Debris Management System Near the Community of Redbird in Whitley County, Kentucky: Lexington, KY, Contract Publications Series 98-09 prepared by Cultural Resource Analysists, Inc., 28 p.

Slavens, Chris, 2017, The Roofed Graves of Delmarva: Laurel Historical Society Newsletter, Winter 2017, p. 4.

Slavens, Christopher, 2020, The Roofed Graves of Delmarva: Laurel, Delaware, Bald Cypress Books, 91 p.

White, Vernon, 2002, Grave Covers: Our Cultural Heritage: Berea, KY, KANA Imprints, 119 p.

Zebley, Frank R., 1947, The Churches of Delaware: (no publisher given), 363 pages.

Special thanks to Janie C. Finch for accompanying me on many of my cemetery survey outings and for her superb proofreading and editing abilities which have greatly improved this manuscript.

Any reader of this paper who knows of the existence of a Tennessee comb cemetery not listed in Appendix A1 or A2 is urged to send this information to the author at rfinch@graterutabaga.com.

Appendix A-2 Comb Cemetery Inventory by County.

Appendix B Limestone Comb Graves.

Appendix C Marble and Shale Comb Graves.

Appendix D Concrete and Concrete Comb Graves.

Appendix E Sheet Metal Comb Graves.

Appendix F Early Comb Grave Dates.

Appendix G Comb Grave Church Associations.

Appendix H Former Comb Cemetery Inventory.